Remembering Frank Mannheimer

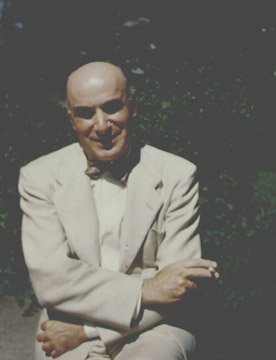

Frank Mannheimer in California in 1951.

Over his long career, Tobias Matthay trained scores of magnificent artists and teachers, and beginning in the 1920s

he began to attract increasing numbers of gifted Americans to his studio on Wimpole Street. But none of his American

teachers ever enjoyed the enduring success of Frank Mannheimer, whose pupils throughout the world

regarded him with reverential awe. Uncle Tobs recognized Frank's unique qualities almost immediately, for he had

a penetrating intellect and a respect for artistry which he transmitted to his students, none of

whom he ever treated in a condescending manner. He had the ability to inspire all who came

into contact with him, and an unusually large number reported that study with Frank Mannheimer marked a decisive

turning point in their personal and professional lives. He was also a master of the "lecture-recital," a

format pioneered by Uncle Tobs, and many remembered the inspirational words and the beautiful playing he offered in

these sessions as some of the highpoints of their musical experiences.

Over his long career, Tobias Matthay trained scores of magnificent artists and teachers, and beginning in the 1920s

he began to attract increasing numbers of gifted Americans to his studio on Wimpole Street. But none of his American

teachers ever enjoyed the enduring success of Frank Mannheimer, whose pupils throughout the world

regarded him with reverential awe. Uncle Tobs recognized Frank's unique qualities almost immediately, for he had

a penetrating intellect and a respect for artistry which he transmitted to his students, none of

whom he ever treated in a condescending manner. He had the ability to inspire all who came

into contact with him, and an unusually large number reported that study with Frank Mannheimer marked a decisive

turning point in their personal and professional lives. He was also a master of the "lecture-recital," a

format pioneered by Uncle Tobs, and many remembered the inspirational words and the beautiful playing he offered in

these sessions as some of the highpoints of their musical experiences.

He taught extensively in Dayton and

in Chicago before he went abroad, and by the early 1920s had acquired a small reputation in the Midwest.

Beginning in the 1930s, he gave a series of summer master classes, first in Chicago, and later

at Cornell College in Mount Vernon, Iowa. The Cornell series was especially successful, and it began to draw students

from all over the country. He had an uncanny ability to "get things done," and one summer he even

brought the Chicago Symphony for concerto performances featuring himself and Myra Hess. He often

told the story of an appearance in Minneapolis in the late 1930s which left him feeling badly

drained and physically exhausted. Following the advice of friends, he went north to Duluth to

rest and he immediately fell in love with this small city on Lake Superior. Originally,

he sought its crisp climate and relative seclusion as a haven away from work, but his reputation

had become so pronounced that several students followed him, at first enduring considerable hardships

to find living accommodations and practice facilities. When the War came and he could no longer

return to England, he took a position at Michigan State University, and his summer class in Duluth

began to grow. After the War, it reached the status of a full-blown summer school, eventually lasting

from May through September. Remarkably, he drew students from all over the country without a

word of advertising, and even more remarkably, he bore all the teaching himself. He typically taught lessons

six days a week for from six to eight hours each day, augmented by at least one weekly lecture-class. This

pattern continued through the summer of 1971 until shortly before his death.

He taught extensively in Dayton and

in Chicago before he went abroad, and by the early 1920s had acquired a small reputation in the Midwest.

Beginning in the 1930s, he gave a series of summer master classes, first in Chicago, and later

at Cornell College in Mount Vernon, Iowa. The Cornell series was especially successful, and it began to draw students

from all over the country. He had an uncanny ability to "get things done," and one summer he even

brought the Chicago Symphony for concerto performances featuring himself and Myra Hess. He often

told the story of an appearance in Minneapolis in the late 1930s which left him feeling badly

drained and physically exhausted. Following the advice of friends, he went north to Duluth to

rest and he immediately fell in love with this small city on Lake Superior. Originally,

he sought its crisp climate and relative seclusion as a haven away from work, but his reputation

had become so pronounced that several students followed him, at first enduring considerable hardships

to find living accommodations and practice facilities. When the War came and he could no longer

return to England, he took a position at Michigan State University, and his summer class in Duluth

began to grow. After the War, it reached the status of a full-blown summer school, eventually lasting

from May through September. Remarkably, he drew students from all over the country without a

word of advertising, and even more remarkably, he bore all the teaching himself. He typically taught lessons

six days a week for from six to eight hours each day, augmented by at least one weekly lecture-class. This

pattern continued through the summer of 1971 until shortly before his death.

Mr. Mannheimer never joined the American Matthay Association.

This is not surprising, since although he never renounced his American citizenship, before

the War he considered England his home, and his participation would have been minimal. For the

most part, he never openly capitalized on his relationship with the Matthay School, but when he

knew the War would prevent him from returning abroad, he identified himself as "Tobias Matthay's

Leading Exponent in America," which undoubtedly created friction with many A.M.A. members.

However, he had a right to this claim, since no other American teacher had apprenticed for such a long

period under Uncle Tobs' supervision, and for many of his American and English pupils, Tobs offered only qualified endorsements.

Shortly after the War, Mr. Mannheimer returned to England, where he re-established himself

as a teacher of international stature. In the early 1950s, he began to show signs of the disease

that would leave him with a permanent tremor, and he concentrated his energies exclusively on teaching,

dividing his time between London, Vienna, and Duluth.

He augmented the income he earned as a teacher with the dividends of investments he shrewdly managed, and he was able to live a comfortable

life, pursuing the activities that mattered most to him. Beginning in the mid-1950s

he became increasingly drawn to the Bay Area

of California, and in the early 1960s he had a beautiful home built on Bennett Valley Road in Santa Rosa, a

residence which he always regretted leaving during his many travels. For the last several

years of his life, Mr. Mannheimer suffered from cancer, but he never complained, and even his

family did not know he was ill until the very end. He died in Dayton in the spring of 1972.

Mr. Mannheimer never joined the American Matthay Association.

This is not surprising, since although he never renounced his American citizenship, before

the War he considered England his home, and his participation would have been minimal. For the

most part, he never openly capitalized on his relationship with the Matthay School, but when he

knew the War would prevent him from returning abroad, he identified himself as "Tobias Matthay's

Leading Exponent in America," which undoubtedly created friction with many A.M.A. members.

However, he had a right to this claim, since no other American teacher had apprenticed for such a long

period under Uncle Tobs' supervision, and for many of his American and English pupils, Tobs offered only qualified endorsements.

Shortly after the War, Mr. Mannheimer returned to England, where he re-established himself

as a teacher of international stature. In the early 1950s, he began to show signs of the disease

that would leave him with a permanent tremor, and he concentrated his energies exclusively on teaching,

dividing his time between London, Vienna, and Duluth.

He augmented the income he earned as a teacher with the dividends of investments he shrewdly managed, and he was able to live a comfortable

life, pursuing the activities that mattered most to him. Beginning in the mid-1950s

he became increasingly drawn to the Bay Area

of California, and in the early 1960s he had a beautiful home built on Bennett Valley Road in Santa Rosa, a

residence which he always regretted leaving during his many travels. For the last several

years of his life, Mr. Mannheimer suffered from cancer, but he never complained, and even his

family did not know he was ill until the very end. He died in Dayton in the spring of 1972.

The International Artist and Teacher

A rare photo of Mr. Mannheimer's summer class at Cornell College in Mount Vernon, Iowa,

in the summer of 1934 or 1935. Many of Uncle Tobs's

pupils were less able to go abroad during the Depression

and welcomed the opportunity to continue their

studies with one of his finest teachers. Long-time A.M.A. member J. Herbert Springer

of Hanover, Pennsylvania, is standing

third from left.

A rare photo of Mr. Mannheimer's summer class at Cornell College in Mount Vernon, Iowa,

in the summer of 1934 or 1935. Many of Uncle Tobs's

pupils were less able to go abroad during the Depression

and welcomed the opportunity to continue their

studies with one of his finest teachers. Long-time A.M.A. member J. Herbert Springer

of Hanover, Pennsylvania, is standing

third from left.

Frank Mannheimer in his London flat in the late 1930s where he did much of his teaching.

When the War broke out, Mr. Mannheimer was greatly saddened that he was forced to be separated from his European friends and students.

This photo taken about 1939 captures the studious, penetrating gaze and thoughtful countenance so well known

to those who studied with him.

When the War broke out, Mr. Mannheimer was greatly saddened that he was forced to be separated from his European friends and students.

This photo taken about 1939 captures the studious, penetrating gaze and thoughtful countenance so well known

to those who studied with him.

On the campus of Michigan State University in the early 1940s

One unexpected benefit of Mr. Mannheimer's Michigan residency during the War years was that

he was

occasionally able to receive his family as guests. He is shown here

in

front of his East Lansing home with his sister, Sara, his older brother, Sol,

and his

mother (foreground). Sara's daughter, Carolyn Slavin,

stands directly behind Mrs. Mannheimer. Dena Mannheimer died on September 1, 1943.

One unexpected benefit of Mr. Mannheimer's Michigan residency during the War years was that

he was

occasionally able to receive his family as guests. He is shown here

in

front of his East Lansing home with his sister, Sara, his older brother, Sol,

and his

mother (foreground). Sara's daughter, Carolyn Slavin,

stands directly behind Mrs. Mannheimer. Dena Mannheimer died on September 1, 1943.

A study in his California home taken in 1968 by Mr. Mannheimer's friend Elizabeth Quandt. She

took

a large number of photos, evidently with the intention of publishing them, but they never saw print.

Mr. Mannheimer's home on Third Street in Duluth—where he taught for nearly thirty years—as

it appeared in the 1990s. Originally built as a carriage house, its rooms were small, and the

beautiful Steinway "D" which sat next to the picture window for so many years, dominated

the living room.

Mr. Mannheimer's home on Third Street in Duluth—where he taught for nearly thirty years—as

it appeared in the 1990s. Originally built as a carriage house, its rooms were small, and the

beautiful Steinway "D" which sat next to the picture window for so many years, dominated

the living room.

Many students remember Mr. Mannheimer's Duluth classes as inspirational and unforgettable.

This photo was taken in the summer of 1961.

Previous Page

Previous Page

Back to American Matthay Association Home Page

Back to American Matthay Association Home Page

©

1999 The American Matthay Association

No text or photos from this web site may be used in other publications

without written

permission from the American Matthay Association

Previous Page

Previous Page Back to American Matthay Association Home Page

Back to American Matthay Association Home Page